UROGYNECOLOGIST, SARA WOOD, MD, MHPE, MEETS WITH A PATIENT TO DISCUSS TREATMENT OPTIONS.

Photography by Gregg Goldman

BY JENNIFER FINK

Pelvic organ prolapse—which occurs when the uterus, bowel, bladder or top of the vagina “drops” or bulges into the vagina—affects one in four women in their 40s, one in three women in their 60s and half of all women in their 80s, according to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

The condition can cause serious discomfort and affect everything from a woman’s ability to work, exercise, control her bowel and bladder function, and engage in sexual activity. Typically, “the first thing women do when they experience prolapse symptoms is stop or limit activities, often out of fear and in reaction to the discomfort symptoms can cause,” says Sara Wood, MD, MHPE, Washington University urogynecologist and chief of the Division of Urogynecology & Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery. Wood treats patients at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Missouri Baptist Medical Center.

That change in activity may be helpful in the short term, Wood says, but it often causes women to shrink their lives. Women who would love to jump on the trampoline with their grandchildren instead watch and wave from a lawn chair. They cancel the 5K they’d planned to run with their sister and text her well wishes on the morning of the race instead. They stop traveling, stay close to home and skip sexual intercourse. And those limitations are in opposition to how we enjoy life.

“We know that the No. 1 thing we can do for our long-term health is to be active,” Wood says. Effective medical and surgical treatment can repair pelvic organ prolapse, allowing women to confidently and comfortably participate in activities they enjoy.

What is pelvic organ prolapse?

Most female urologic and reproductive organs—the bladder, uterus (or womb) and vagina—are “held in place by a hammock of muscles called the pelvic floor,” according to the National Institutes of Health. The bowel is supported by this hammock of muscles as well. When the muscles and tissues supporting these organs become weak or loose, they sag. And just as your body will swing closer to the ground if you lay in a stretched-out hammock versus a brand-new one, the organs supported by a weak pelvic floor may drop lower, too.

Illustration courtesy of Shutterstock

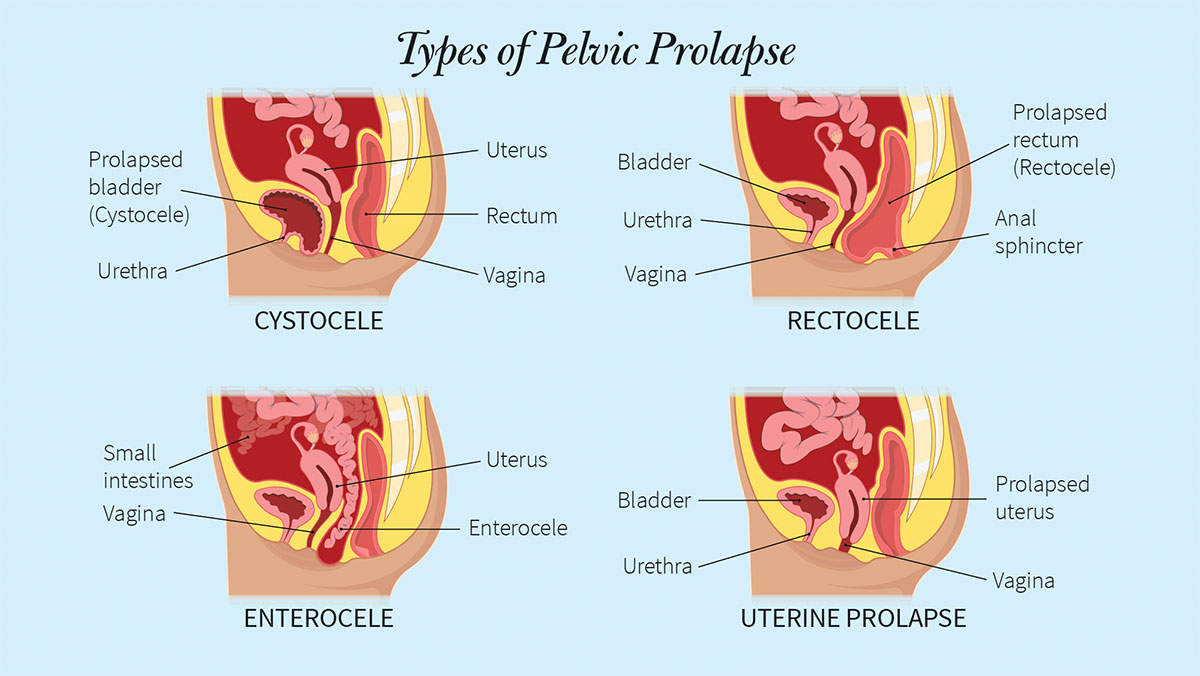

The bladder, uterus, rectum (a part of the bowel) and top section of the vagina can drop out of place and bulge into the vaginal canal. A dropped bladder, a condition known as cystocele, is the most common type of pelvic organ prolapse. Uterine prolapse (sometimes called a dropped uterus or prolapsed uterus) affects approximately 50% of women who have given birth.

Rectocele (bulging of the rectum into the vagina) and enterocele (prolapse of the small bowel) are less common forms of pelvic organ prolapse; however, an individual can experience the prolapse of multiple pelvic organs.

Pregnancy and vaginal childbirth increase the risk of pelvic organ prolapse, but women who have never conceived can also experience pelvic organ prolapse, as can women who have had C-sections. Prolapse is even possible after hysterectomy, the surgical removal of the uterus. Other risk factors for pelvic organ prolapse include aging, long-term increased intra-abdominal pressure (which may be caused by chronic constipation, coughing or obesity) and family history.

“There is growing evidence that there may be some genetic risk factors for prolapse,” says Jerry Lowder, MD, MSc, Washington University urogynecologist at Barnes-Jewish Hospital. However, he notes, it’s not yet possible to use testing to determine whether a woman is likely to develop prolapse. Lowder also treats patients at Missouri Baptist Medical Center.

The hormonal changes associated with menopause may accelerate the development of prolapse. “Estrogen plays an important role in the support of the connective tissue, so women who are experiencing a loss of estrogen may have a more rapid progression,” Lowder notes.

Symptoms of pelvic organ prolapse include a feeling of pressure, discomfort, aching or fullness in the vagina, which may get worse with activity and improve with rest. Some women (or their partners) see or feel “something” in the vagina or at the vaginal opening. Individuals with pelvic organ prolapse may also experience urinary leakage and difficulty with bowel movements. And some may find sexual activity or tampon insertion uncomfortable or difficult.

THE ABILITY TO RESTORE A WOMAN’S QUALITY OF LIFE IS WHAT DREW ME TO THIS WORK. WE HELP WOMEN GET BACK TO THE LIFE THEY WANT TO LIVE

Prolapse can range from mild and asymptomatic to severe and impossible to ignore. “About 40% to 50% of women will have some degree of pelvic organ prolapse on physical examination,” Lowder says.

Pelvic organ prolapse that does not cause symptoms or distress may not require treatment. Most individuals who have symptoms related to pelvic organ prolapse could benefit from medical or surgical treatment.

UROGYNECOLOGISTS SARA WOOD, MD, MHPE, AND JERRY LOWDER, MD, MSC

Photography by Gregg Goldman

Shame, stigma delay treatment

The symptoms of pelvic organ prolapse “tend to be very marginalizing for women,” Wood says, noting that women “may be embarrassed to talk about it. There might even be a degree of shame that is associated with it.”

That embarrassment and shame can be exacerbated by a culture that freely uses images of young-looking, vibrant, active women yet is more apt to discuss male erectile dysfunction than female sexual health. As a result, women experiencing prolapse symptoms can be reluctant to discuss or disclose the reality of their aging bodies.

“When the uterus or vagina begins to drop and come through the vaginal opening, that can create a real sense of isolation for women,” Wood adds.

Self-esteem can plummet. A research study led by Lowder found that women living with prolapse are, he says, “more likely to feel self-conscious, isolated, less feminine and less attractive. Their connection to their spouse or partner may suffer, and some women with prolapse avoid sexual intimacy all together.”

Wood notes that some women begin experiencing symptoms in their early 40s yet may not seek care until they are in their 60s and prolapse has progressed. “A woman may have bothersome symptoms but delay seeking evaluation and care from a urogynecologist because she assumes her condition may be “just part of the aging process,’ or she may feel her life is too busy to seek treatment,” Wood says. “We want to educate and empower women to speak up, share their symptoms and seek treatment earlier.”

In many cases, women quietly tolerate worsening symptoms for decades, gradually adapting their lives in limiting ways. Pelvic organ prolapse is not life-threatening, so postponing treatment isn’t harmful. But the most frequent comment Wood hears from women after she surgically repairs their pelvic organ prolapse is, “I wish I’d done this sooner.”

Treatment improves quality of life

When pelvic prolapse is treated, it can result in the resolution or minimization of symptoms, allowing women to return to their favorite activities.

Wood encourages women who have “stopped doing the things that they enjoy” due to symptoms of prolapse to seek diagnosis and a treatment plan. Proper assessment is key to effective management because urinary leakage, for instance, is treated differently if it’s caused by an overactive bladder rather than pelvic organ prolapse. A urogynecologist, a doctor trained in obstetrics and gynecology who specializes in the care and treatment of pelvic floor disorders, can identify the degree and exact location of prolapse. This information can then be used to determine appropriate treatment options.

Some pelvic floor disorders are managed with physical therapy; other treatment options include surgical repair and the use of a pessary, a medical device that’s used to support prolapsed pelvic organs.

“A pessary is kind of like a knee brace,” Lowder says. “It will treat the symptoms of the underlying condition and add support, but the underlying condition is still there.” Like a knee brace, it must be fitted to the patient, and it only provides support when in use. A pessary is a good option for people who can’t or would rather not undergo surgery. Some women choose to use a pessary to manage their symptoms while waiting for an opportune time to undergo surgical correction.

A range of surgical approaches are available, and it’s up to the patient and surgeon to determine the treatment that best fits the condition and the patient’s desires.

“A surgeon will first determine which support defects are present, then design and explain an appropriate surgery suited to the patient,” Lowder says. The patient’s medical history, overall health, values and goals also play a role in treatment selection.

Broadly speaking, there are a few types of surgeries used to repair pelvic organ prolapse. Surgeons can use a vaginal or abdominal approach and either native tissue or surgical mesh to support sagging organs.

“We can offer a range of minimally invasive surgical options, including a vaginal approach with no incisions made through the abdomen, and a laparoscopic approach using small abdominal incisions,” Wood says. Surgical closure of the vaginal opening is yet another option for women who no longer wish to have vaginal intercourse.

“We personalize our surgical approach to the patient,” Lowder says, noting that repair of pelvic organ prolapse is usually a well-tolerated, same-day procedure. Patients typically recover and recuperate from the comfort of their own homes, and most women are back to their usual activities within a few weeks. Two months after surgery, many can do things they haven’t done in years. Most women report a significant improvement in function and body image after surgery.

“The ability to restore a woman’s quality of life is what drew me to this work,” Wood says. “We help women get back to the life they want to live.”

If you believe you have a pelvic floor disorder, schedule an appointment for a comprehensive evaluation with a Washington University urogynecologist by calling 314-747-1402.